Turkish Islamic arts

in Türkiye

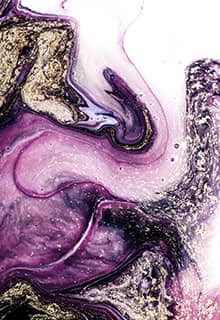

Marbling

The art of marbling, or Ebru in Turkish, is the art of creating colorful patterns by sprinkling and brushing color pigments into a shallow tray with water and then transferring the patterns to paper. The designs and effects include flowers, foliage, ornamentation, latticework, mosques, and moons, and are mostly used for decoration in the traditional art of bookbinding. Although it is not known when and in which country the art of marbling was born, there is no doubt that it is a decorative art peculiar to Eastern countries. Several Persian sources report that it first emerged in India. It was carried from India to Persia, and from there to the Ottomans. According to other sources, the art of marbling was born in the city of Bukhara in Turkistan (in modern-day Uzbekistan), finding its way to the Ottomans by way of Persia. In the West, Ebru is known as ‘‘Turkish marbling.’’

Woodworking

The art of woodworking developed in Anatolia during the Seljuk period and formed its own unique characteristics. The Seljuks, who were master woodcarvers, generally used wood for mosques and wardrobe doors. Their designs mainly included vegetal geometric designs (star compositions) and calligraphy. Figures are rarely seen. The Seljuk woodworking techniques include carving, kündekari,kalemişi, and openwork applique.

Ottoman products were rather plainer. In the Ottoman period, wood was used for household goods such as tripods, drawers, chests, spoons, thrones, Quran protectors, and architectural features such as windows, doors, joists, consoles, column heads, ceilings, mosque niches, and minbars.

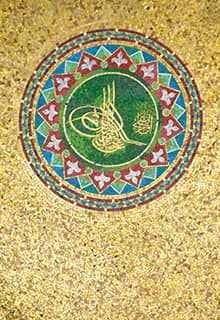

Illumination and Gilding

Known as ‘‘tezhip’’ in Turkish, gilding is an old decorative art. The word ‘‘tezhip’’ means ‘‘turning gold’’ or ‘‘covering with gold leaf’’ in Arabic. However, tezhip can be executed with both paint and gold leaf. It was mostly employed in manuscripts and on the edges of calligraphic texts.

The art of illumination has been practiced as widely in the West as it has in the East. In the Middle Ages, it was widely used to decorate religious texts and prayer books. Gradually, however, figural illustrations became more popular, and illumination became restricted to the decorated capital letters at the start of religious texts.

Among the Turks, the history of illumination goes back to the 9th century. The Seljuks brought it to Anatolia, and illumination reached an apogee in Ottoman times. In the 18th century, the Ottoman art of illumination began to fade, with crude decoration replacing the classical motifs. In the 19th century, the Western influence that could be seen in almost all areas of art, began to make its presence felt in the art of illumination as well.

Calligraphy

Calligraphy emerged after a long period between the 6th and 10th centuries as Arabic letters evolved. In addition to the six principle styles of Islamic calligraphy, the Turks created a new style from the ‘‘talik’’ form discovered by the Persians. Turkish calligraphy continued to flourish in the 19th and 20th centuries. With the adoption of the Latin alphabet in 1928, however, it ceased to be a popular art form and with time, it became a traditional art that is taught in specialized schools and institutions.

Miniatures

Miniatures are an art style with a long history in both the Eastern and Western worlds. There are those, however, who maintain that it was originally an Eastern art, from where it made its way to the West. Eastern and Western miniature art is very similar, although differences can be observed in color, form, and subject matter. The scale was kept small since the art was used to decorate books.

In the Seljuk period, great importance was attached to miniature painting. During Ottoman times, the Seljuk and Persian influence continued to the 18th century. At that time, the best-known miniaturists were Mustafa Çelebi, Selimiyeli Reşid, Süleyman Çelebi, and Levni. Among them, Levni marked a turning point in Turkish miniature painting. He moved beyond traditional conceptualizations and developed his own unique style. Under the influence of the renewal movements of the 19th century, Western art also began to affect the art of miniature painting in Ottoman lands.

In Türkiye, the art of miniature painting used to be called ‘‘nakış’’ or ‘‘tasvir’’ with the former being more commonly employed. The artist was known as a ‘‘nakkaş’’ or ‘‘musavvir.’’ Miniature work was generally applied to paper, ivory, and similar materials. In time, miniatures slowly began to give way to contemporary art as we understand the concept today.

Glasswork

Distinguished examples of glasswork left behind by Anatolian civilizations illuminate the history of glass today. Stained glass in various shapes and forms was developed in the Seljuk period. During the reign of the Seljuks, the most important glass was a gilded honey-colored flat glass platter with an everted rim. A sample of such a platter was found during excavations at Kubadabad.

After the capture of Constantinople, the city became the center for glasswork. Ceşm-i Bülbül and Beykoz are two of the Ottoman techniques that survive to this day. Accessories and artifacts such as oil lamps, tulip vases, sugar bowls, stained glass panels, and goblets were made using these techniques.

The first examples of beads to ward off the evil eye (nazar boncuğu) made of glass were produced in the village of Görece in the province of İzmir. Today, evil eye beads can be seen in every corner of Anatolia. It is believed that all living creatures and non-living things can be protected from the evil eye by such beads. These beads are believed to divert malicious glances containing the evil eye elsewhere. Amulets to ward off the evil eye are, therefore, put in places where everyone can easily see them.

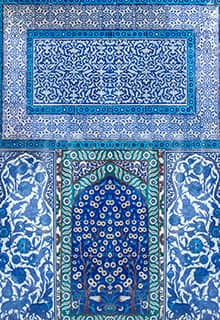

Tile Making

The art of tile making, which developed in connection with architecture, entered Anatolia with the Seljuks. The main color of glazed tiles used in Seljuk minarets and tombs is turquoise. After the first half of the 13th century, aubergine purple and cobalt blue can also be found. In the Seljuk period, flat tile plaques were usually used on the walls and relief tiles were used for inscriptions. Curved surfaces such as vaults and domes were covered with tile mosaics, whose main colors were turquoise, dark blue, purple, and white.

The main tile-producing center from the mid-14th century to the end of the 17th century was İznik. From the mid-14th century to the mid-15th century, “red paste” tiles were produced in İznik and its surroundings.

Embroidery

Embroidery is the ornamentation of materials such as leather, cloth, or felt with silk, wool, linen, cotton, and metal threads. The art of Turkish embroidery has a long history. Embroidery began in the palace, and later become a decorative folk art.

The embroidery techniques and needles that are used today are the end product of many changes based on economic and geographic conditions and aesthetic considerations. Turkish embroidery techniques vary according to the way the needle is used: the needle may be applied to the woven threads or to pull out the woven threads; needles may help to close the threads (Buhara atması [lit. Bukhara knot], Jakobyen atması [lit. Jacobean weft], Maraş işi [lit. Maraş work], applique), or to bind the threads (patchwork, kumru gözü [lit. dove eye], Antep işi [lit. Antep work], geçme işi, etc.).

Turkish Literature

Following the adoption of Islam by the Karakhanid prince Satuq Bughra Khan in the mid-10th century, the Turkish world began to enter the orbit of a new civilization. The Turkish tribes that migrated westward carried the influence of that civilization into the world of literature. Starting from the late 11thcentury, written literary tradition spread among the Seljuks.

Kutadgu Bilig, Divanü Lugati't-Türk, the written works of Yunus Emre, and Evliya Çelebi’s Seyahatname(Book of Travels) are among the best-known examples of Turkish literature between the 11th and 13thcenturies. Ali Şir Nevai (Ali-Shir Nava’i) developed Chagatai Turkish as a rich language of art and culture.

The golden age of Ottoman literature lasted from the 15th century to the 18th century, and included mostly divan poetry but also some prose works. The literature developed along two separate lines: court literature and popular literature.

Court Literature

The literature developed by Ottoman intellectuals, who were principally raised in amadrasa (an educational institution that was part of a mosque complex) and who took Arab and especially Persian literature as their role models, is known as ‘‘court literature.’’ It is also referred to as “zümre edebiyatı” [loosely translated as high-class literature] or ‘‘Islamic age’’ Turkish literature.

Popular Literature

This genre consists of folk tales, folk songs, proverbs and riddles, the creators of which are either hard to determine or unknown. Dervish literature can be regarded as popular literature with a religious content. Mysticism's broad tolerance and manner of expression resulted in the emergence of an independent strand within this literary tradition.

Anatolian Rugs (Turkish Carpets)

The term “Anatolian rug” is a term of convenience, commonly used today to denote rugs and carpets woven in Anatolia (or Asia Minor) and its adjacent regions. Together with the flat-woven kilim, Anatolian rugs represent an essential part of the regional culture, which is officially understood as the culture of Türkiye today and which derives from the ethnic, religious, and cultural pluralism of one of the most ancient centers of human civilization.

The arrival of Islam and the development of Islamic arts profoundly influenced Anatolian rug designs. The ornaments and patterns reflect the political history and social diversity of this area. However, scientific research to this day has been unable to attribute any particular design feature to a specific ethnic or regional tradition, or even to differentiate between nomadic and village design patterns.

The Seljuks began weaving carpets in the 11th century and carpet weaving became an important industry in Konya, Sivas, Kayseri, and Aksaray. Seljuk carpets are often of considerable size and are made of sheep wool.

In Europe, Anatolian rugs were frequently depicted in Renaissance paintings and were considered symbols of elevated dignity, prestige, and luxury. Political contacts and trade intensified between Western Europe and the Islamic world after the 13th century. When direct trade was established with the Ottoman Empire during the 14th century, all kinds of carpets were indiscriminately given the trade name of ‘‘Turkish’’ carpets, regardless of their actual place of manufacture.

Important Turkish Rug Motifs

Elibelinde

The motif symbolizes not only maternity and fertility but also luck, fortune, happiness, and joy. It is the symbol of femininity.

Hayat Ağacı

The motif symbolizes eternity.

Muska

The motif reduces the effect of the evil eye and protects the owner from bad events.

Bereket

The motif symbolizes eternal happiness and abundance.

Important centers of rug production in Türkiye

Marmara Türkiye: İstanbul, Hereke, Çanakkale

Aegean Türkiye: Bergama, Uşak, Milas, Kula, Gördes, Megri

Central Türkiye: Konya, Kayseri, Niğde, Sivas

Eastern Türkiye: Kars